The Blair Witch Project became a global sensation in 1999 by ingeniously presenting itself as the authentic recovered video recordings of three student filmmakers who had vanished. Its phenomenal success was powered by a fusion of raw horror and a revolutionary internet marketing campaign that masterfully built a mythos around the film’s supposed reality. In the dial-up era of the late ’90s, its official website offered fabricated police reports and news interviews, convincing a generation of moviegoers that the terrifying events they were witnessing were genuine. This powerful combination of filmmaking and marketing cemented the movie’s place in history, creating a cinematic language that would define a subgenre for decades to come in films like [REC], Paranormal Activity, and Cloverfield.

The Blair Witch Project‘s influence is undeniable, and its reputation as a genre trailblazer is well-earned. Directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez created a landmark of immersive horror by prioritizing authenticity above all else, going as far as dropping actors into the woods with minimum instructions, just to secretly film their real fear and despair. However, the techniques and narrative structure that made the film a phenomenon were not born in the Maryland woods. They were the culmination of a long, often controversial, and incredibly varied cinematic history.

So, while The Blair Witch Project stands as the ultimate popularizer of found footage, its roots stretch back through decades of exploitation cinema, political filmmaking, and technological innovation.

Cannibal Holocaust Is a Controversial Found-Footage Predecessor

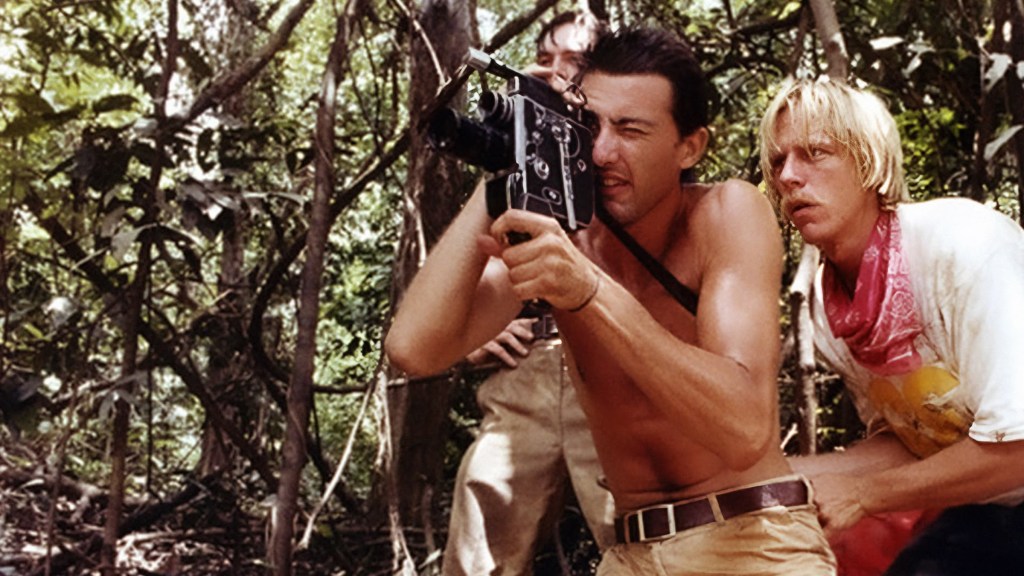

Nearly two decades before The Blair Witch Project, the deeply disturbing groundwork for the found footage genre was laid by Italian director Ruggero Deodato’s 1980 film, Cannibal Holocaust. The story follows an American anthropologist who ventures into the Amazon rainforest to discover the fate of a missing documentary crew. His discovery of their lost film canisters leads to the film’s second half, which consists entirely of viewing this recovered footage. That means the audience watches, alongside the anthropologist, the gruesome story of the filmmakers’ demise at the hands of a remote tribe. This narrative device, a story told through the unedited recordings left behind by deceased subjects, represents the genre’s absolute core conceit.

Deodato’s commitment to the illusion of reality was shocking. He employed grainy 16mm film stock, shot in remote and unfamiliar locations, and used indigenous actors who were unknown to Western audiences to heighten the film’s documentary-style plausibility. The resulting footage felt so distressingly real that Italian authorities charged Deodato with murder, believing he had actually killed his cast on screen. He was only exonerated after producing the actors in court and demonstrating the gruesome special effects he had used in Cannibal Holocaust.

Despite its structural innovation, Cannibal Holocaust’s legacy is stained by its indefensible inclusion of real animal cruelty. This horrific production history has made the film impossible to champion without significant caveats. As a result, while Cannibal Holocaust is arguably the true progenitor of found footage horror as we know it, its controversial choices have largely prevented it from being widely celebrated, leaving the door open for The Blair Witch Project to later define the genre for the mainstream. However, there were other important stepping stones before the Blair Witch was conjured on the silver screen.

The Home Video Revolution in Horror

The aesthetic of found footage took a significant leap forward with the widespread availability of consumer camcorders. This technological shift democratized the “found” media, moving it from professional film reels to the family home video. A crucial and often overlooked milestone from this era is the 1989 direct-to-video movie UFO Abduction. Presented as a single, unedited home video shot during a child’s birthday party, the film documents a family’s horrifying encounter with extraterrestrials. Its use of the mundane setting brilliantly grounds the extraordinary events in a familiar reality, while the chaotic first-person perspective makes the viewer feel less like they are watching a film and more like they are a trapped guest at the party as it descends into terror.

This home-video approach was further refined nearly a decade later by the 1998 independent feature The Last Broadcast. Its premise is remarkably similar to its more famous successor, The Blair Witch Project, presenting itself as a documentary investigating the murder of two public-access TV hosts in the New Jersey Pine Barrens. The story is pieced together using the crew’s recovered digital recordings. The film was also a technical trailblazer, standing as one of the first features to be shot, edited, and distributed entirely with consumer-level digital equipment.

Though it predated Blair Witch by a full year and shared many of its elements, The Last Broadcast never achieved mainstream success. The critical difference was in its presentation. It frames its recovered footage within a conventional mockumentary structure, complete with a narrator and formal interviews, creating a safe analytical distance for the viewer. The Blair Witch Project‘s genius was the complete removal of that safety net. It presented only the raw footage itself, with no external guide or narrator to hold the audience’s hand, totally immersing the audience in the characters’ terrifying experience and thus becoming a genre-defining film.

The Distant Roots of Found Footage Horror Movies

While films like Cannibal Holocaust and UFO Abduction established the specific horror conventions that led to The Blair Witch Project, the fundamental concept of presenting fiction as reality is much older. The power of found footage comes from its ability to co-opt a trusted medium, and this idea was masterfully explored long before the advent of consumer camcorders. As such, the genre’s true ideological origins can be traced back to pioneering media experiments and the rise of the mockumentary, which taught filmmakers how to leverage the language of truth to tell a powerful lie.

One of the earliest and most famous examples was Orson Welles’ 1938 radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds. As part of his Mercury Theatre on the Air anthology series, Welles structured the H.G. Wells story as a typical evening music program that was suddenly interrupted by a series of increasingly frantic news bulletins. These reports detailed a terrifying Martian invasion unfolding in real time. The broadcast perfectly mimicked the tone and format of live news reporting, which was the most trusted source of immediate information in the pre-television era. Despite a disclaimer at the start of the show, a portion of the audience who tuned in late believed they were hearing an actual news event.

This technique of using documentary conventions for fictional purposes was later formalized into the mockumentary genre, with filmmaker Peter Watkins as one of its most important pioneers. His 1966 film The War Game, which depicted a nuclear attack on the UK in the stark style of a government newsreel, was so harrowing and realistic that the BBC banned it from television for two decades. His 1971 film Punishment Park pushed the form further, presenting a fictional scenario where political dissidents are hunted in the desert by law enforcement, all captured by an impartial European news crew. By adopting the observational language of cinéma vérité, Watkins forced audiences to confront his political arguments not as fiction, but as a brutal reality they were witnessing firsthand.

Found footage is a direct and logical evolution of the mockumentary tradition. It takes the core principle of mimicking a non-fiction format and pushes it to its scariest conclusion. It strips away the final layers of documentary artifice, such as an omniscient narrator, formal interviews, or explanatory title cards, presenting only the primary source material. Plus, the “found” nature of the footage inherently implies that something has gone horribly wrong and that the audience is sifting through the aftermath. The Blair Witch Project became a cultural landmark because it was a perfect synthesis of these distinct traditions. It took the brutal horror premise from Cannibal Holocaust, the intimate home-video aesthetic from UFO Abduction, and the powerful reality-bending ethos pioneered by media hoaxes and political mockumentaries, and forged them into an unforgettable experience.

What was your introduction to the found footage genre? Let us know in the comments!

The post What Is the First Found Footage Movie? Well, It’s Complicated appeared first on ComicBook.com.