Shooting two or more films back to back is really nothing new. It’s been done since the ’30s. Then, in the ’70s, it started happening with bigger movies, movies based on pre-existing IPs. It’s as if the studios behind them knew there was a high probability for success so they decided to get a sequel out there literally as soon as possible. Of course, it’s more complicated than that in reality. There are multiple motivations for shooting two (or three, in rare cases) movies at once. Sometimes it’s logistics, such as having access to remote shooting locations, and sometimes it’s the aforementioned desire to strike while the iron is hot.

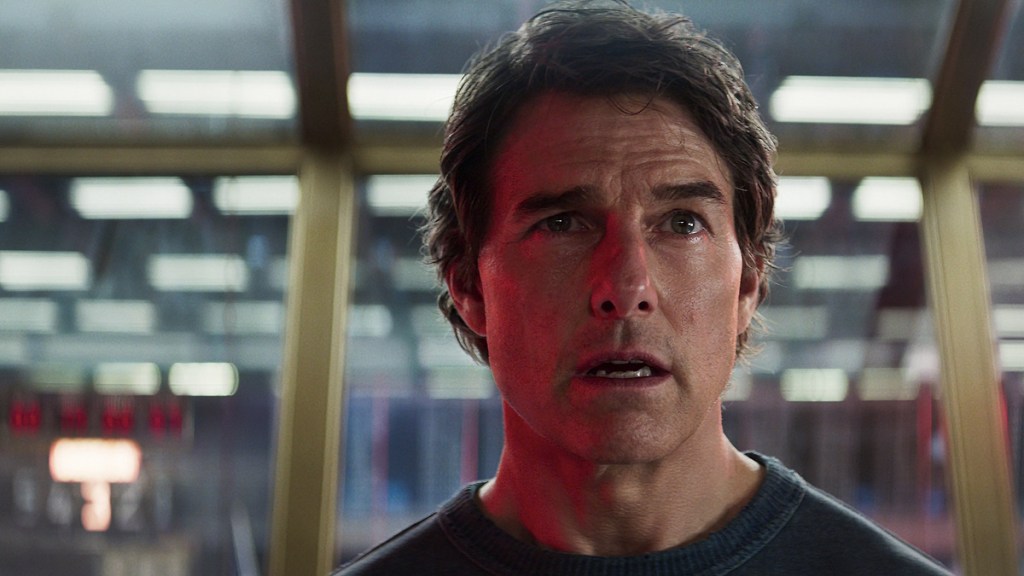

Either way, it’s a gamble that seldom has paid off. For instance, with the Mission: Impossible franchise and its one-two combination of Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One (as it was initially called) and Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning.

The Early Days of Back-to-Back Filming

Let’s stick to the ’70s for the time being. The Three Musketeers and The Four Musketeers, for instance, were shot as one mega film and were then split in post-production. It was just too much for a single movie.

But with Richard Donner’s Superman and the mostly Donner-helmed Superman II, it really was an example of the studio and filmmakers knowing there were two stories to tell, they would be too much for a single movie, and that the first of those two movies was likely going to be a success, so why not get the second one out there ASAP. This was a tactic utilized by smaller production companies throughout the ’80s, most notably The Cannon Group for their first two Missing in Action movies and the Indiana Jones rip-offs King Solomon’s Mines and Allan Quartermain and the Lost City of Gold.

Those latter two examples are indicative of a problem with the tactic. Just because two movies are going to be produced doesn’t mean even the first one is going to be all that impressive, or that there’s even a clear plan in place for them. For instance, Missing in Action 2: The Beginning was supposed to be the first film, but those behind it realized it was weak, even by The Cannon Group standards, so it was shuffled to second. If there isn’t a clear vision for where one 90- or 120-minute narrative should go and what it should be, there certainly isn’t going to be one for two movies.

Filming Sequels Back to Back

Using the back-to-back tactic to get sequels out would seem to solve the problem on the surface. But does it? On one hand, parts two and three wouldn’t exist without the success of part one, which ostensibly was a success that was not only large enough to warrant the investment in two movies but also the faith in those two movies’ similar success. Better yet, the first movie wouldn’t have been such a success if it hadn’t done a solid job of establishing a world the audience enjoyed and wanted more of.

This would seem to indicate that movies two and three could just continue what worked the first time around. But the simple truth is, just because something worked amazingly once doesn’t mean it’s going to work two more times. The result is often a trilogy consisting of a fantastic opening chapter and two other chapters that feel like watered-down, pale imitations.

The first major Hollywood property to attempt the back-to-back sequel filming tactic was Back to the Future. And, while Back to the Future Part II and Back to the Future Part III do feel slightly independent from one another, it’s not enough. They feel like stories just hanging on the first film’s stories with a tightly gripping single hand.

The next time it was attempted (save for the continuous filming of The Lord of the Rings trilogy, which worked like a charm) was for The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions. There, it was a problem quite dissimilar from the one experienced by Back to the Future. Specifically, Reloaded and Revolutions felt like they were tied to another far more than they were tied to The Matrix, all the while again feeling like extra-bombastic and overly elaborate variations of what worked the first time around. The same applies to Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest and Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End. Though, admittedly, those two sequels receive far more hate than they deserve.

Direct Comparisons to Mission: Impossible

The best example in terms of tying things back to Mission: Impossible is the Harry Potter film series. Like with Mission: Impossible, the two Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows movies serve as the conclusion of a long-running series (for both the Mission: Impossible and Harry Potter movies, the final two chapters were the seventh and eighth installments overall).

To a degree, it worked for Harry Potter the same way it worked, to a degree, for Mission: Impossible. The question is whether “to a degree” is enough. At the end of the day, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1 feels like exactly what it is: half of a movie.

[RELATED: 7 Standalone Action Movies to Watch if You Love the Mission Impossible Franchise]

The difference is that the back-to-back filming method made a certain amount of sense for Deathly Hallows. It was a pre-existing work with a lot of ground to cover in a single two-and-a-half-hour movie. Mission: Impossible wasn’t bound to anything other than the first six films. There was no pressing need to shoot Dead Reckoning and The Final Reckoning as one long movie.

Furthermore, Mission: Impossible is an example of how this tactic is a massive gamble. Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One cost an absolutely staggering $291 million. That’s before marketing costs are even factored in. And, even with COVID in the rearview mirror, it drastically underperformed. Were The Final Reckoning not already well into production, it could have resulted in Mission: Impossible ending the same way as The Divergent Saga. In other words, basically not ending so much as just stopping.

Given its anticipated opening of nearly $80 million across four days, The Final Reckoning is likely going to perform a bit better than Dead Reckoning, but it also comes with a price tag of at least $300 million, possibly upwards of $400 million. It practically needs to generate at least $1 billion in worldwide ticket sales just to break even. That’s a tall order, and one that shines a light on just how risky it is to invest massive sums in two “separate” projects simultaneously.

The Risks of the Method

There’s a reason it’s called The Final Reckoning and not Dead Reckoning Part Two, after all, and that reason is Dead Reckoning Part One‘s underperformance. That in and of itself illuminates the other problematic element of filming blockbusters back-to-back. For one, if the first part underperforms, it’s highly unlikely the second part is going to rebound enough to make the overall investment worth it for the studio. Two, what fans end up with are two middling installments, not two independent movies with distinct visions going into their construction from the ground up.

Now, all of this is not to say Dead Reckoning and The Final Reckoning are weak films. They’re far from it. They’re visually stunning, they come equipped with engrossing set pieces, and they’re both well-directed and well-acted. It’s just they fall short of highpoints like, well, the three installments that preceded them: Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol, Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation, and Mission: Impossible – Fallout.

Those three movies felt bound to the overarching story of Ethan Hunt without going out of their way to do so, and they certainly didn’t feel inextricably bound to one another. With Dead Reckoning, you’re better off having seen everything but Mission: Impossible 2. And with The Final Reckoning, it’s the same thing with the added element of it being imperative you’ve seen Dead Reckoning. It never operates independently, which inherently doesn’t bode well for it having the strongest possible legs at the box office throughout subsequent weekends.

There’s merit to ambition in filmmaking. However, when studios are funneling money into two sequels at once, it’s important to make sure the two sequels are not only true to everything that’s come before, but also to one another. If not, there’s no point in binge-watching the two as one mega movie, which is the majority of the appeal in filming sequels this way.

Hence the aforementioned defense of Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest and At World’s End. Dead Man’s Chest leads very well into At World’s End. And, while they’re somewhat different tonally, it’s not enough to be jarring, just the same as their overall tone isn’t all that different from what was established in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl. That’s just not the case with the final two Mission: Impossible movies, which seldom feel like two parts of a whole. The end result is really just two sequels that don’t live up to the three more individualized sequels that preceded them.

The post Mission: Impossible Proves That Hollywood Needs to Kill This Moviemaking Trend Forever appeared first on ComicBook.com.