When Skybound Entertainment first announced in 2021 that acclaimed cartoonist Tillie Walden would write a trilogy of YA graphic novels set in The Walking Dead‘s universe, many fans, both those of The Walking Dead and other who had read Walden’s graphic novels Spinning, On a Sunbeam, and Are You Listening?, were surprised. The Walking Dead fans hadn’t expected the grisly world of The Walking Dead comics to grow to include a YA subseries, let alone one that brought back the popular protagonist of The Walking Dead video game series, and those familiar with Walden’s intimate, relationship-focused work didn’t expect to find the artist – who had previously published only entirely original – telling a story with someone else’s intellectual property.

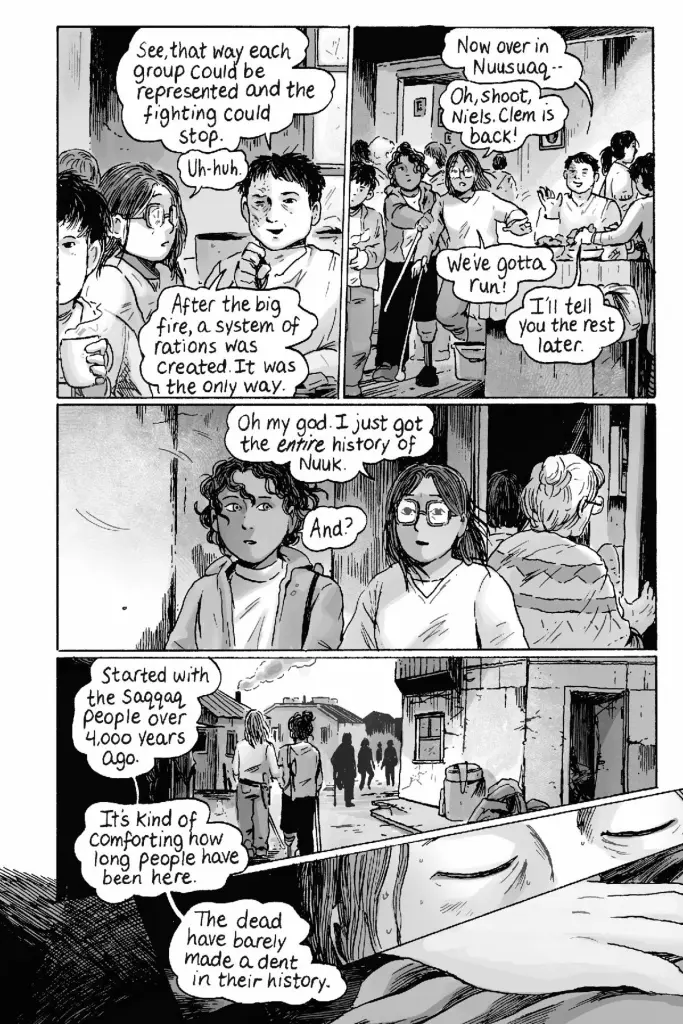

But now, the Clementine trilogy is complete. Clementine Book Three was released in comic shops in June and in bookstores everywhere this week. Having already seen Clementine and her friends survive a hostile mountaintop and deceptively serene island, Clementine Book Three sees the group struggling to find their place in one of the new communities that have sprung up in the wake of the zombie apocalypse. At the same time, Clementine continues to navigate the trauma of her childhood, along with fresher mental and emotional wounds.

ComicBook had the opportunity to speak with Walden about the Clementine series upon the release of its final installment. During the discussion, she touches on the themes she tried to weave throughout the trilogy, the new skills she learned along the way, and why she was disappointed about the lack of cholera. Be warned that the conversation does brush up against spoiling at least one major event in Clementine Book Three. Our conversation follows.

When you started work on Clementine, as you went in on Book One, how thoroughly did you have the whole three-book story worked out? Was it all there?

No. It was almost all not there. It was. I came up with a plot for Book One, and Book One alone, right at the start. I was like, “Let’s do Vermont. Let’s do some evil twins. Let’s do our little dance where two girls are going to like each other. I built all that, and it was only as I was working on the inking that my editor was like, “By the way, what’s the plan for number two? What’s the plan for number three?” And I was like, “I don’t know. Why are you asking me that? I’m making book one. You have to be patient.” And I waited all the way until Book One was wrapped and done before I started thinking about Book Two and, while I was working on Book Two, I did start considering Book Three, just a bit, just because, as a middle book of a series, you’re laying the groundwork for what’s gonna happen in the next one.

But I didn’t think about Book Three as much as I should have. If I could go back in time, in my time machine, I would tell Tilly of Book One of Clementine, “Take an hour. Write down some ideas. Give yourself some structure.” It would have saved me a lot of redrafting because, by not planning the series out, it meant that it was a really tall order for each book to fully connect to the first, but also fully build on it. Book Two got redrawn a few times, and Book Three got redrawn a few times, all because I didn’t plan what I should have planned.

The only idea I had while working on Book One, fleetingly, was that I knew that, at some point in the series, I wanted Clementine to go back to school, and I wasn’t able to pull it off in Book Two, but I was like, “I want it to happen in Book Three,” and that was the only anchor point that I knew about. The rest was really coming up with it as I was working on it.

Why was sending Clementine back to school so important? Why was that such an anchor point for you?

As I was working on Book One – and especially as I was working on the dialog – Clementine, Ricca, Amos, Olivia, Georgia, they read things, they talk about their past, and it really started to dawn on me that reading would be hard for them if you stopped at second grade. You can read in second grade, but you can’t read big words; you’re an early reader, and the more I thought about it, I was just like, “Oh God. Can these kids even write their names? When’s the last time she picked up a pencil?”

And it really stuck in my head, because I found it affecting to think about this idea that these kids are so much more proficient than I am in a lot of ways – they can build a fire, they can kill a moose, they can survive – but they know nothing about math, about history, about language, about reading, about media. It really stuck in my head, and then I was then I was like, “Oh, well, that’s something I have to do then is I have to reintroduce this to her,” because I think so much about this series is about Clementine becoming a whole person and not just being a survivor, and I think one of the ways you you become a whole person is what you learn from others, and we all get that by going to school.

I really craved the idea of her sitting at a desk again, because I felt like it would be so weird, as someone who has just spent the last 10 years doing nothing but killing and running and being hungry, to sit at a desk and have someone give you a worksheet. How out of left field. So, I got my wish. I got to do it in Book Three.

I think that’s such a funny thing about kids and about teenagers, and even young adults, is you become a master of what you’ve experienced but everything outside of that experience, you don’t know what’s going on, and that’s what adulthood is, learning to handle experiences you’re not used to. But these kids, no, they have no idea what is in store for them.

Along those lines, I was struck throughout the series by some of the words the kids don’t know, because they’re not the kind of words you’re necessarily taught, they’re the kind of words most kids would take in almost by osmosis from being around others.

Yeah, as a series too, I’ve spent a lot of time with Clementine hanging out with other kids her age. She doesn’t hang out with a lot of adults. I think that there would be a really fascinating generational divide in the post-apocalyptic zombie universe, because I think that the people who grew up with nice, cushy childhoods with running water, these kids would have no patience for them. They’d be like, “You don’t know this world like we do.” So I’ve kept her sequestered with a lot of young people, which means she spent all her time with other uneducated young people, so all the stuff that I think she could have picked up naturally, she didn’t.

Going back to my previous question, I’m a little surprised to hear you say that you didn’t have much planned out when you started the series because I re-read the first two books before reading Book Three, and I felt like I could see patterns emerge, with Clementine going throguh these different stages of development, first rebuilding herself, then learning to have a relationship with one person, and then learning to fit into a community. And then also, the villains are so similar — not villains, they’re more antagonists — but they all feel like Mirror Universe versions of Clementine, or at least who Clementine could have turned out to be. Were those conscious choices you made, or did they emerge more naturally as you wrote, or am I seeing patterns that aren’t there?

I was definitely chasing patterns. Even though it wasn’t written in advance, when I was writing Book Two, it was so defined by what I had written in Book One. It was conscious that Georgia was technically the villain of Book One, and then in Book Two, what if this villain grew up? What if this villain becomes a woman who’s lost? Who doesn’t know how to handle herself or her community? Then that’s Miss Morro. Then in Book Three, it was like, “Okay, well, what? What would Miss Morrow have been like if she had found community, if she had found people who love her and cultivated that love, but that love was toxic?”

All of it, I think, ends up being that these books have themes of womanhood, of coming of age, of all the different ways people deal with trauma. So I really consciously came back to the same themes again and again, like themes of memory of the past kept coming up with school, with Ricca being interested in Judaism, with Olivia learning to have a baby, with Clementine learning to be in a relationship, it’s all the same story. I think that helped, and it made it possible to write this series one at a time, because I was always leaning on these same themes and same questions. And every book, I just wanted to attack the themes from a different angle, always trying to do something a little bit differently. The different settings really helped with that, because if the setting is different and we have new characters, then it gives me a new reflection point to examine Clementine, and to examine her friends.

Learning that you didn’t have it all planned out at once also means that you didn’t know – and we’re dancing around spoilers here, so reader beware – what would happen with Ricca in Book Three until you were writing it.

That I did come up with a little bit in Book Two — I had an inkling that that was gonna happen.

So, when and how did that occur to you? What made you feel like this was a thing that needed to happen for Clementine’s story to end? What clicked that into place?

You know what? I think it happened around when I was about to give birth to my son. When you’re getting ready to give birth – you don’t have to do this, but you do have to, sort of – you get your ducks in a row in case you do not live. People sometimes die in childbirth, and my wife and I considered, if we both die, who’s going to take care of our kid? And all of these questions, and I think the proximity to new life brings about such proximity to death.

It made me realize that I actually think the crowning trauma, the scariest thing that Clementine has not experienced, is death that just happens, and I think that the kids of the apocalypse would have a really intense vision of how people are taken from us. It would be visceral. They would be ripped from our lives. We would often see it happen. It would be bloody, but it would be very clear. I think that in a safe modern society, one of the most painful things about death is that we don’t always understand it, and it is so unexplained and scary, and there have been people in my life, a person, a very young person in my wife’s family who had two pulmonary embolisms all of a sudden. It was horrifying. She’s okay, but it was like, “Oh my god.” I worked as an EMT for a while, which gave me a really close view of the tenuousness, the fragility of life.

I actually think of how much more difficult a loss would be for them when you don’t bleed, when you don’t have the gash, the wound, when you don’t have someone to blame. I think that it’s actually really helpful, traumatically speaking, for all these kids in the apocalypse that you just take your anger and you put it back on the zombies, because they’re the ones who took your loved ones, or a person took your loved one, and you put your anger on them.

But the universe is mysterious, and we do not always have someone to blame. And I felt like, as soon as that idea hit my head, I was like, “I know it needs to happen.” And I actually think that if you asked my editor, he would probably say that I had been gently musing about this idea maybe all the way back in Book One. So it was always a possibility. It’s just like me thinking about death and about how hard it would be for a kid of the apocalypse to not know about pulmonary embolism, and so, yeah, it just happens. You would drop dead. There is no way to stop it.

It’s such a contrast from the main The Walking Dead series, in that there’s such intentionality behind death there. For death to just happen because sometimes death just happens feels almost revelatory in that context.

It’s so unfair! It feels like it doesn’t fit! It’s like it’s is the wrong story. This is not how things are supposed to go, and that’s why I felt like it was the ultimate challenge for Clementine and the ultimate challenge for me as a writer is to square that this is an experience I’m going to have someday. I am going to see this end that these characters are seeing, and I’m terrified, but the only thing that gives me comfort is that every other human being on this Earth is staring down the same end that I am. I feel like the fact that we’re all going through it together is the way I can live on in the face of that.

Another interesting contrast with The Walking Dead – or maybe it’s more how Clementine complements The Walking Dead – is in how Clementine takes some of The Walking Dead’s big ideas and themes and makes them intimate. To me, the first half of The Walking Dead is a lot of bad stuff happening, and then the second half is about rebuilding in the aftermath, all on a societal level. And here, with Clementine, it feels like a lot of bad stuff happened to her in the video games, and your stories are about her rebuilding in a similar way, but internally – how do you rebuild a person who has been through so much trauma?

Yeah, and what’s so cool is that, before I worked on these books, I had subconsciously been writing stories about rebuilding again and again. In On a Sunbeam, they’re rebuilding all these old buildings all over outer space, which I have been quietly obsessed with the notion of building architecture and the spaces we create for ourselves, the families we create for ourselves. These themes had been interesting to me for a while, and it just worked so well when this Walking Dead series came knocking on my door, because it was like, “What is this series going to be about? It’s going to be about a kid rebuilding herself and rebuilding the world with her friends in their image.” I was like, “This is perfect.” This is already interesting to me. It’s still interesting. There is no amount of stories about people building something or building themselves that I will get sick of. It’s perpetually fascinating.

I think that it was so fun to contrast and to juxtapose Clementine’s inner rebuilding with the rebuilding of the world around her, because there’s just so much detritus and decay in the zombie apocalypse. It was so fun to consider all the ways societies would rebuild themselves and would function. And as I’m sure you can tell in this series, I harbor a lot of interest in the chores people would do and the ways people would do things. If anything, I held back quite a lot.

My whole goal with Book Two was to just write a book about cholera. I really wanted to, I was really concerned about the sewage situation in The Walking Dead universe, because everyone has been shitting outside, and every time you kill a zombie, that body is going to sit there and rot and get in the water, so there is probably nothing but fetid water everywhere in North America. Where Is anyone getting clean water? Everyone would die of cholera. So I wanted to make Book Two about cholera. My editor was like, “We can’t make a book about cholera. Can you make it about something other than human waste?” And I was like, “Fine. Way to creatively stifle me. I guess I’ll make a different book.” But it’s okay. It’s not about human waste, but I wanted, in Book Two, the crowning achievement to be that they create a plumbing and water purification system. But that doesn’t really drive the plot that much. I don’t think.

This series is your first time playing in somebody else’s creative sandbox, so to speak. Were you at all reluctant about doing something like this, and has the experience made you more or less eager to do something similar again in the future?

I didn’t go into it with any reluctance, because I was coming off an era of having done quite a few original graphic novels. I had finished Are You Listening? and I was like, to be honest, a bit ready to take a break from my own voice, and a bit ready to take a break from this kind of house style I had been coming to through Spinning and through Sunbeam and through Are You Listening? And I felt like this came at the perfect time, because I was seeking constraints, and I wanted to get out of my comfort zone, and I felt like working on IP, working in this universe that is not my own, working on a universe that has quite a legacy, quite a fan base, where a woman has never drawn it, never written it, I was like, “This sounds like a really interesting challenge.” So I was pumped. I was super excited, and I loved that.

Most people’s reaction to it was like, “Tillie Walden is doing a Walking Dead book?” I was like, “That’s perfect. I love that sentence. That’s hilarious. I never would have guessed.” And also I felt really proud, because I couldn’t believe that I’d gotten to a place in my career where they would ask me to do this. It was moving. It felt like, wow, I am somebody in this field. This is really cool. This is a huge opportunity. So I was nothing but excited.

Now, on the other side of it, after having dealt with a pretty intense fan backlash, I don’t even know what to call it, I am a little hesitant to work in someone else’s sandbox again for a while. I think I got, in a way, a raw deal, because I wasn’t truly dealing with Walking Dead fans, I was dealing with video game fans, and if GamerGate taught us anything, video game fandom, while it can be super important and amazing for a lot of people, it can be really, really toxic. So I don’t think I’m going to work on anything connected to a video game ever again, to be quite honest.

I harbor no regret about working on these books. I love them, I’m proud of them, and I’m so happy to say that Skybound and Robert Kirkman have been fully supportive of me and been on my side and looked out for me, but I don’t want to get death threats anymore. I don’t want to get death threats over a fictional girl who’s not real. That’s ridiculous. That is a useless waste of time and emotion. I don’t need that in my life, and I don’t look at a lot of it. I am totally fine, but if I can avoid it, I will. I think that if I work on a property, a universe, an IP again, I would have to be ready, and I would want to understand the fan culture before I go into it.

I think working on these books for me, as a creator, has been a really enlightening experience and really improved who I am as a writer and as an artist, and it’s been a really, I think, cool era for me and my work. Now, as I step back into more original graphic novels and different things. I think it’s all going to be influenced by the work I did on Clementine.

Can you talk about that a bit more? I read another interview from around the time that the first book came out, and you talked about how you had to learn how to draw zombies, because that was not something you really knew how to do. Are there specific skills, things that have affected your art, that you’ve learned through this series, that you expect are going to influence what’s coming next?

Oh, yeah. I have gotten so much more comfortable and better at drawing action. Obviously, a huge part of The Walking Dead comic book series is beautiful inking, a lot of spot blacks, a lot of this sort of shadow, dark texture, and I learned so much about inking. I learned so much about style working on these books, and I can see it evolve through Clementine Book One, Two, and Three.

It’s funny, the book I’m working on right now is like the polar opposite. There is not any action in sight. It’s historical, and it’s very calm, because these women were very calm, but I can feel what I learned. I can feel how I learned to draw characters in space with one another in new ways, and it’s just night and day. I have so many new tools in my tool belt. It’s really awesome, because if I’d spent this time doing more classic books like I’d done before, yeah, I’d still be great at drawing trees and boats and some Victorian-looking houses, but I wouldn’t have learned this. I wouldn’t have learned about running, hitting, moving, all this more classic comic book style stuff. I love old-school inking. I love this legacy of where comic books come from. And no, it doesn’t read very well now, but I love Dick Tracy. I love the old world style of cartooning, and I it was fun to touch upon it in this, a little bit.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Clementine Book Three is on sale now.

The post Tillie Walden Concludes Her Walking Dead Journey With Clementine Book Three appeared first on ComicBook.com.