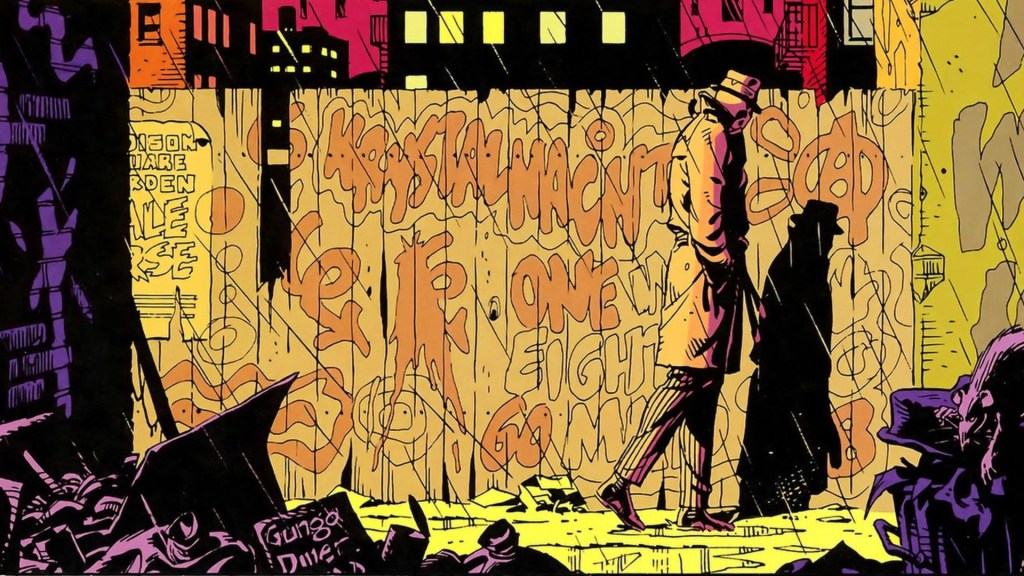

Alan Moore is widely considered the most talented writer to work in the comic medium. Moore’s writing changed the comic industry forever, and though he’s made the transition away from the comic industry, he’s still a brilliant writer (I would argue even more so, but I’m a Jerusalem superfan.) Moore’s works were never anything less than ambitious, and he created so many straight up brilliant series. The work Moore is most known for is Watchmen. Watchmen revolutionized superheroes by deconstructing them, taking those icons we look up to and showing that they were just like us, their neuroses driving them to places few people go. Watchmen taught that the gods are human, and maybe we shouldn’t trust them as much as we seem to. It’s an amazing work, one that has been replicated many times but never duplicated. Well, until the 2010s.

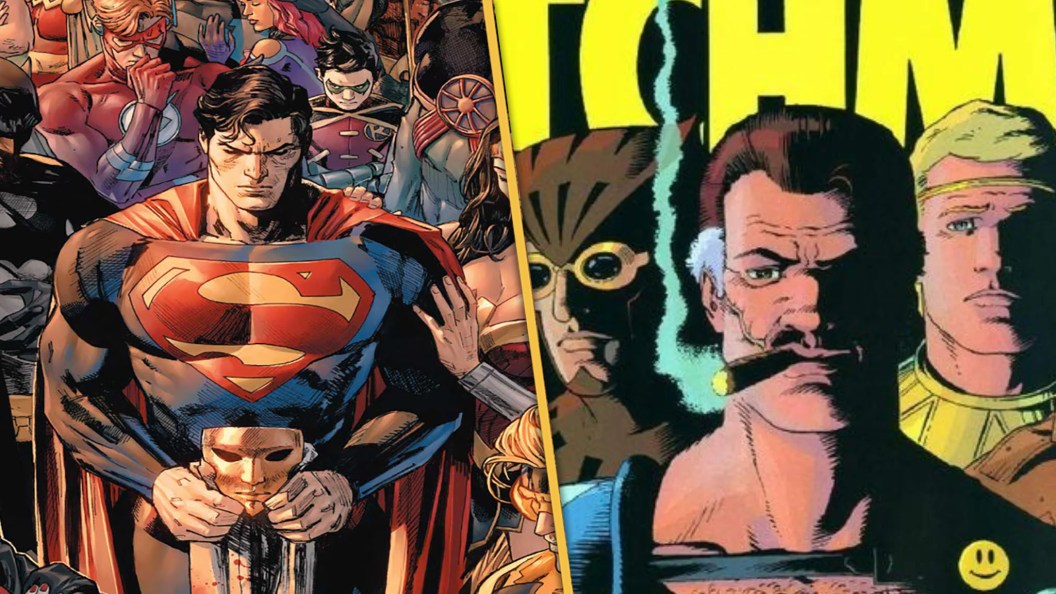

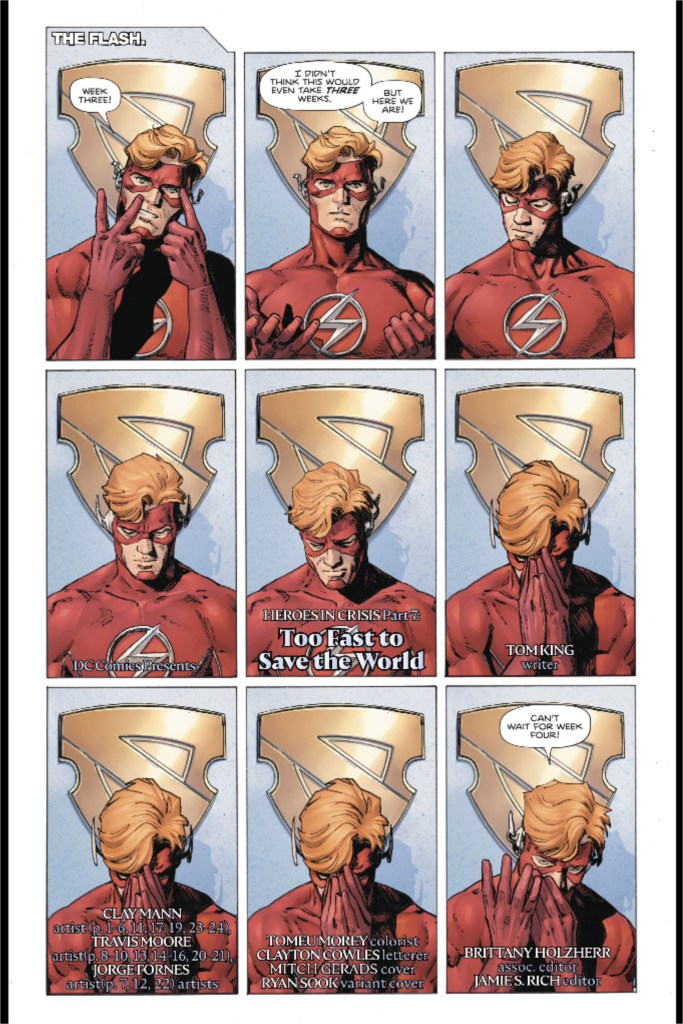

While many writers have tried superhero deconstruction in the years since Moore made it absurdly popular, only one has been able to get close to Moore in one of their more maligned works. I’m speaking of Tom King. King rose through the ranks to writing Batman, but his most believed works are his miniseries. The announcement of a Mister Miracle animated series based on King’s work, and the fact that he was made showrunner, shows that King has the goods. However, we aren’t here to talk about the masterpiece Mister Miracle. No, today, we’re going to talk about King’s most controversial work — Heroes in Crisis. This highly maligned series usually tops lists of worst DC Comics events, but I would argue that there’s some good to it — King’s deconstruction of the superheroes of the DC Universe. In fact, I would say that it’s the best example of superhero deconstruction since Watchmen.

Watchmen and Heroes in Crisis Both Showed Superheroes at Their Most Human

I’m not going to argue that Heroes in Crisis is on the same level as Watchmen, because that’s a fool’s errand. Watchmen stands tall among the greatest comics of all time, a brilliant work that cinched the maturation of the comic medium. Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ seminal work is basically flawless. The writing and art are at a level that few comics can match, and calling it the best comic ever feels wrong, because it’s so much better than nearly every other comic ever made. The only problem with Watchmen has nothing to do with the story; the problem is that we’ve been told how great it is for so long by so many people that we trust that people have started to rebel against it. Watchmen is on a level that it created, and while we all have stories that we like more than Watchmen, no one is going to argue against its bona fides. Heroes in Crisis, on the other hand, basically has no cheerleaders.

Heroes in Crisis was first announced as Sanctuary. King had become known for his psychological storytelling, and Sanctuary was going to focus on a superhero mental health facility. This was the germ of the idea that would become Heroes in Crisis. The problems with Heroes in Crisis are manifold. It’s an interesting enough murder mystery, but then you get scenes where Harley Quinn is somehow able to escape Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman. However, Booster Gold and Harley work well together, Blue Beetle and Booster are awesome, and the book excels in one place — the testimonial sections where the heroes talk about their problems. In fact, pretty much every issue set in Sanctuary, with the heroes using the facility as a place where they can talk about the tremendous pressures of their job is spectacular reading. Heroes in Crisis, in its own way, did something similar to Watchmen. It was interesting to see DC’s greatest heroes talking about their feelings. Fans of King’s writing enjoy this aspect of it, as the psychology of a superhero — a person who in most cases would be have major PTSD — is quite interesting.

However, there’s a difference in the reason Moore deconstructs superheroes and the reason King does so. For Moore, it’s part of his anarchistic outlook on the world. One of the hallmarks of Moore’s work in general is the humanization of these mythological beings. Look at his Swamp Thing. Moore is the one who made Swamp Thing into god when it comes to power level, but also went further than anyone else to show the human side of him. Moore may have taken away Swamp Thing’s “humanity”, but in the process made him more of a fully realized person. Moore’s Superman in “For the Man Who Has Everything” is one whose secret desire is to just be a normal person. Doctor Manhattan is a god, but he still has the powerlessness of a human because he sees time as something happening, not as something he can affect. Moore wants to show that superheroes are human, to show us that not only can we reach their heights of goodness, but also that we shouldn’t put them on the pedestals. So much of Moore’s work is about this — that the powers that be are only powers because we let them be, and we shouldn’t let them.

King’s work, on the other hand, seems to be more about showing that superheroes are fallible as a way to work through his own feelings on his CIA work. Look, I’m not the first person to say this, but right when I learned about King’s background in the War of Terror, his characters made perfect sense. When you think of a CIA agent, what do you think of? A shadowy power in the darkness, something more than a regular soldier, right? These are people who have taken on a mystique. My interpretation of King’s work, especially Heroes in Crisis, is that he’s doing this to deal with his own guilt. To show that everyone gets messed up when they have to do the kinds of things that superheroes in the DC Multiverse and intelligence agents in the real world have to do. It’s another example of demystification. You have to remember, when King joined the CIA, we were in the midst of the War on Terror. The United States cast its armed forces, and intelligence groups, as heroes fighting a war of survival against an implacable foe. People were told they would be heroes for joining. They committed atrocities. They were anything but heroic, even if their work did conceivably save lives.

I can’t really comment on King’s own opinions, only what I can see of his work. King wants to show us that these people we look up to, these people in positions of power pay a price for what they are. It comes from a very different place than Moore’s own version of superhero deconstruction, but in the end, the results are the same — we see our heroes as us. Heroes in Crisis isn’t on the same level as Watchmen is when it comes to quality. While reviews of a thing are usually subjective, the general consensus is that Watchmen is better than Heroes in Crisis. However, both of them serve the same purpose — to show that our gods are humans, with all of the issues and pain that entails. Those issues and pain are often why they join the fight.

King and Moore’s Work Comes From the Same Place

Alan Moore has always been something of an iconoclast. Moore is a Baby Boomer, and watched his home country become more and more conservative throughout the ’70s and ’80s. Much of his work looks into the world he grew up in and how its changed. His work has always been that of an aging hippie, still going on about the world that his generation failed to build. King’s work has always come from a different place. Moore’s work is almost always political in some way, where’s King’s isn’t. King doesn’t try to make any grand pronouncements about society, and doesn’t use superheroes to deal with “issues” like Moore did. I like to think that King knows the disdain that many fans hold for him because of his past, so he doesn’t even attempt to talk politics with his work. King is more about showing the pains of those who have done the hardest things to survive.

Watchmen is a complicated narrative, about people in extraordinary situations that’s also completely of its time. Anyone who knows anything about the ’80s can see where it takes a look at the decade of excess. Heroes in Crisis doesn’t do anything as noble as Watchmen. It was a story that then-DC head honcho Dan DiDio used to devalue Wally West as a character, and made some choices with its characters that are honestly indefensible in places. However, the light it shines on the minds of superheroes, of what all of this horror would do to them, is exactly the same light that Watchmen shines on them.

You can say what you want about Heroes in Crisis and Tom King, but you can’t deny what the story does for superheroes. It’s a shining example of bringing the greatest heroes in the DC Multiverse down to the level of the readers. I’ll never understand what it’s like to have my existence completely wiped from reality, but I do understand great loss. One of the few good things about Heroes in Crisis is the way it humanized so many heroes. Much like Watchmen, it shows the consequences of extraordinary lives. It shows the sins we commit to fix the problems that we cause.

King stories like Mister Miracle, The Vision, Batman, Human Target, Supergirl: Woman of Tomorrow, and more all deal with showing that the heroes we looked up to in more human lights. Moore’s work does the same thing. Both of them break characters down to their constituent parts, showing the humanity within them. I can’t tell you to like King’s work or to look at it as on par with Moore’s. As writers, all they really have in common is that they both wrote the best Watchmen stories (I will die on the hill of King and Jorge Fornes’s Rorschach is the only great non-Moore written Watchmen comic project). However, if you look at the way both of their works deconstruct the legends we love, there’s a throughline that’s undeniable.

What do you think about Moore and King? Sound off in the comments below.

The post Is Tom King the Alan Moore For Millennial Comics Readers? appeared first on ComicBook.com.